Bayes' Rule (in real life)

Motivating example

Let's say you're a doctor. A woman with no symptoms comes into your office after she's tested positive for breast cancer. Let's say the prevalence of breast cancer at her age is in . Imagine we have a test that is accurate when the person has cancer and accurate when they don't have cancer.

We often refer to as the "sensitivity" (since it's how sensitive the test is to the disease). We call the , "specificity", since it's how specific the test is for the disease.

The woman is stressed out that she tested positive. She asks you, "How likely is it that I have breast cancer?" Is the answer 10% or 90%? Many people make the mistake of saying . The actual probability is . This article will explain why, and how to avoid this mistake.

A perspective on why this is wrong

My dad came up with a great way to think about it. Imagine a population of 1000 people and do the calculations on that. You know the prior is , so people have cancer, and people don't. Our test is accurate when they have cancer; so, people who have cancer test positive, and person who has cancer tests negative. Of the , our test is accurate, so about people test negative, and about people test positive.

We know the woman tested positive, so she is either one of who has it, or who doesn't have it. so she is about likely to have cancer. That was a lot of calculation, and directly applying Bayes' rule isn't much simpler. We will create a framework for making these kinds of decisions that is mathematically sound, and easy to use in real life, even if you don't like math.

An aside about odds

You may have heard your friends bet on something with odds (or even odds). This means the event has a chance of happening. It is similar to the idea of "parts" in a cooking recipe, "3 parts water" and "2 parts wine" means the mixture will be wine. It's exactly the same happening here. is , is about , odds are . The idea is to go from the odds of: "it happens times": "it happens times", we go

This is how you can convert odds to probability.

You can convert probability to odds using the following formula. Let's say the probability of an event happening is . The odds of it happening are

One nice thing about odds is you can cancel out common factors, so

How do we fix our intuition?

You should think about the test–-not as determining if she has breast cancer–-but as updating your guess that she has breast cancer. Since the prevalence of breast cancer at her age (with no symptoms) is she has the odds of breast cancer of .

Now, apply this formula (with representing odds):

So,

Thus, the chance that she has the disease is about . This is the key formula that you should use in your everyday life. It allows to you quickly incorporate more evidence into your calculation, or change your prior odds.

Where the hell does this come from? Don't worry, I will explain.

You ask: Why is the formula you presented remotely true???

Intuitively, think about the waterfall analogy

If the only thing we care about is the odds at the end (i.e. the ratio of red to blue at the bottom), then we only need to care about the odds that it goes in, or Since they are the same odds, we end up with red to blue in both cases.

The proof

We start with our prior odds, cancer:not cancer, which is written

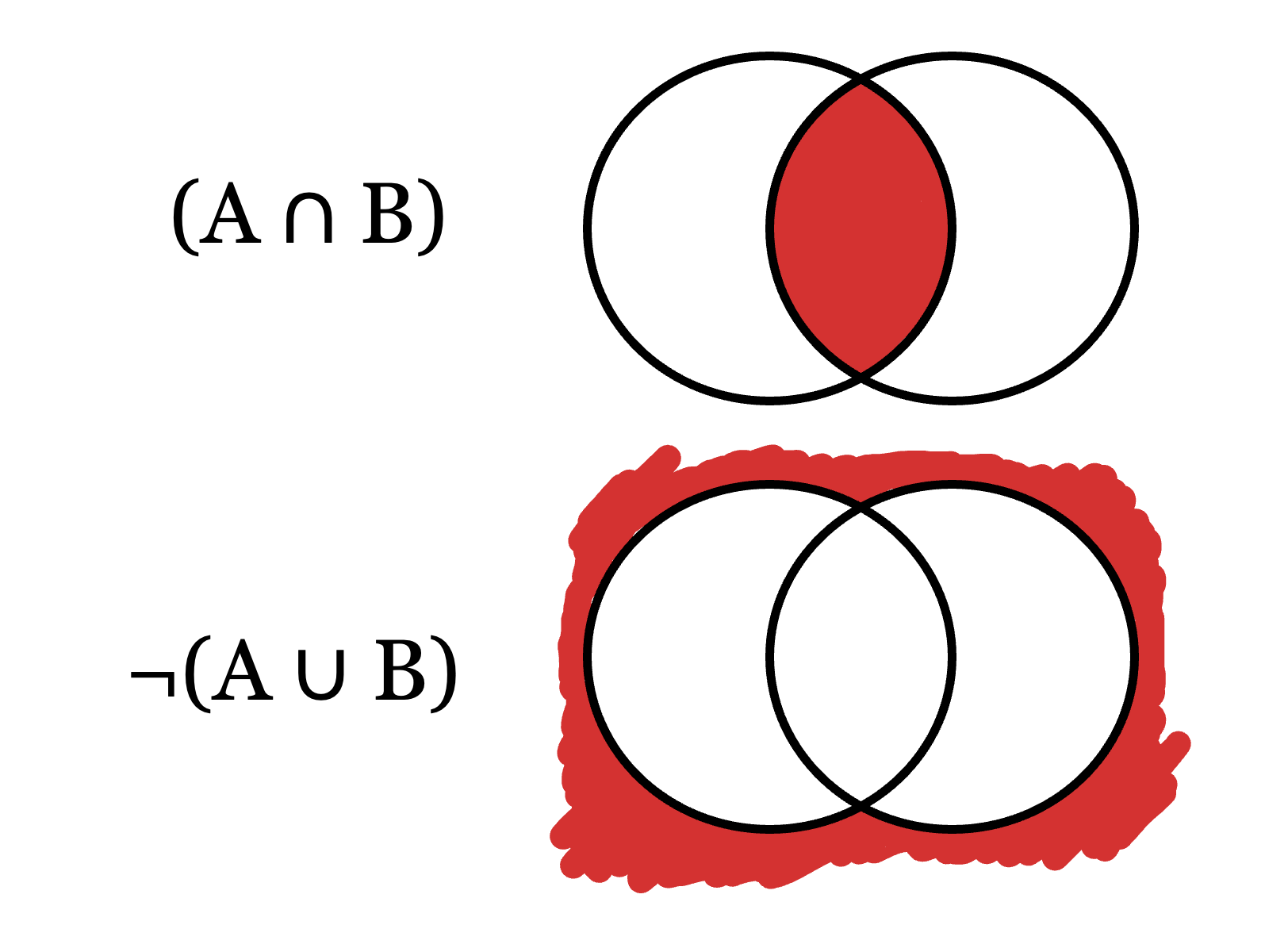

We want to know the probability of cancer given she is positive. In probability form, we write that This kind of conditional probability is really important to understand, and I can't explain it too thoroughly here, but the idea is when you say "A given B", you are restricting your universe of possible events to only ones where B is true, and you're asking, out of those times, how often is A true. That is, We can rewrite this as . This formula will be very important. You should also know that we can rename the A's to B's, so . We will use this later.

The odds we want to know about can be written . This will tell us our new estimate of the likelihood that the woman has cancer, given that she tested positive.

I claim that the question mark is true.

Here is the proof:

The last wrinkle to that calculation I showed earlier is how to calculate The trick is that usually this is given to you or easy to calculate. is the false positive rate, which if the test is accurate when they don't have cancer is . And , which is the true positive rate, or sensitivity of the test, . Thus, the

It should be clear now, that

This formula is amazing because it is very easy to add more evidence to update your understanding.

Let's say you reassure the woman. "It was a routine checkup, you have no symptoms, we just need to run another test, it was probably a mistake." She does it again and comes back positive again. Now, she should start to get worried:

Almost even odds. Okay, sure, but let's imagine that the second test came back negative. To understand the odds, we need to calculate the odds for a negative test. Try this on your own and I'll see you in the next paragraph.

Now, let's calculate this,

This isn't as nice and round a number, but it allows us to calculate:

Another great thing about this, is let's say we get more information that the prevalence in her age group is actually . How do we incorporate that? Well, it replaces our prior estimate. So, rather than . Now,

Unrelated: What does multiplying odds usually do?

The rule can be justified as follows:

This might be better understood by a very poorly drawn PowerPoint slide: