Solving the Game of 24

Solving the Game of 24

I was first introduced to the game by a friend at a coffee table on a Sunday. They were surprised that I'd never heard of it. 24 is a mathematical game where you use basic arithmetic operations to make four numbers equal 24.

The premise is given 4 playing cards, race to find an expression equal to 24. So if you were given \(2\), \(3\), \(6\), \(4\), one solution is \((6-3)\times 2+4=24\). Another example is if you had \(4\), \(8\), \(1\), \(9\), one solution might be \((4\times 8)-9+1=24\). I usually take out the face cards or count them as 10.

However, there's lots of games where I can't find a solution. For example, \(10\), \(10\), \(10\), \(10\), is there any way to make \(24\) with that? What about \(5\), \(5\), \(5\), \(1\)? I had to know what the solution was so I set off to create an algorithm.

The Brute Force Solution

My initial approach was to consider all possible arithmetic expressions (the brute force approach). It's the simplest possible strategy. We just guess and check every option. It works because even an iPhone can process thousands of these expressions in a second.

There are 3 pieces to this. An expression will look something like this: \(x_1\circ (x_2\circ x_3) \circ x_4\), where \(\circ\) can represent any of the arithmetic operations (\(+,-,\times ,\div ,\textasciicircum\)).

The \(x_i\)'s can be any of the 4 numbers

We can put any of the 5 arithmetic operations in between the numbers

(this is subtle) we can put parenthesis around any of the operations to potentially change the value

We tackle each of these 3 separately. To get all possible variable assignments, we know it will be all possible permutations of the numbers. There are \(4! = 4\cdot 3\cdot 2\cdot 1= 24\) permutations for 4 elements. This is true because when you're putting the numbers in, the first place has 4 options, then in each of the universes where you chose one, there are 3 options remaining for the next place, then in all those universes there are 2, etc. Thus, we just need to list out all permutations to get all the \(x_i\)'s assigned to all numbers.

To get all possible choices of operators, it's even simpler: we have 5 options for the first operator spot, then 5 options again, and another 5 options again. So, \(125\) possible options.

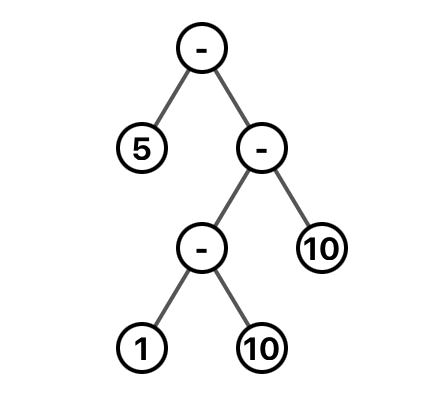

The parentheses one is trickier. The way I approached this problem is you can draw out the order of operations in a tree:

A tree diagram unambiguously tells you how to calculate an expression, in the same way that parenthesis does. If you saw \(5-1-10-10\) there's a way to parenthesize this to get \(24\): \(5-(1-10-10)\), but if you did it in the PEMDAS left-to-right you'd get \(-16\). We need that specificity to express all of the options.

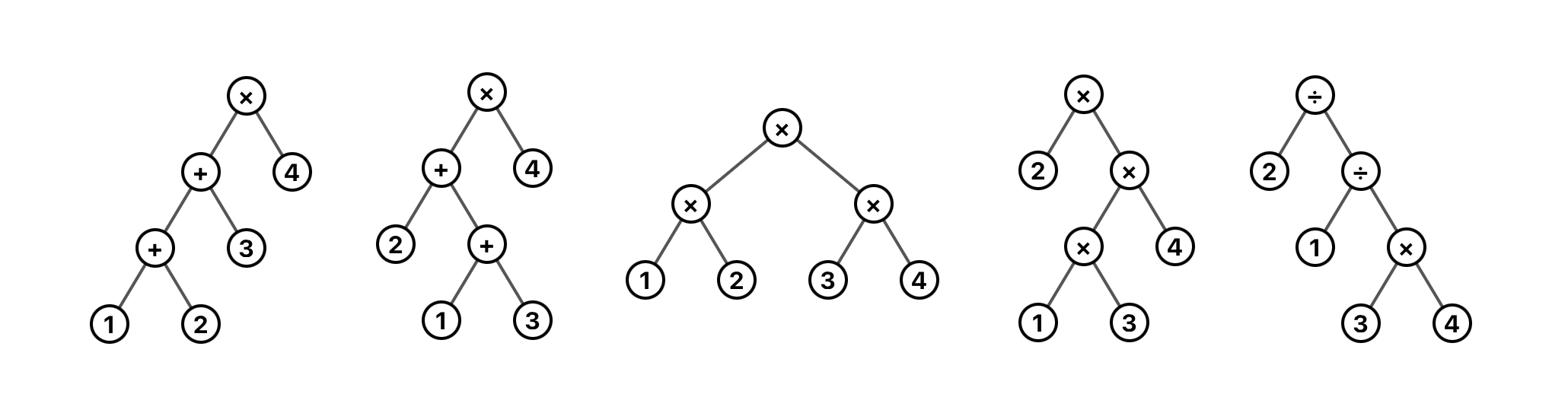

There are only 5 tree base shapes[1] (I've included a brief proof in the footnotes). It may also be intuitive that these are the only tree shapes you can make. Regardless, if we look at every option for all 3 of these aspects of arithmetic expression we get \(15,000\) total trees, and a straightforward way to list them all out.

In the code this ends up playing out like the snippet below. You loop through every permutation for 4 elements, every list of 3 operations, and every tree type and use that to construct a tree.

for (const perm of permutations(4)) {

for (const op_list of cartesianPower(ops, 3)) {

for (const tree_type of treeTypes) {

... construct(perm(nums), tree_type, op_list) ...

}

}

}If you're interested in the code for how that works, the loop is in App.jsx (full code here).

What I Discovered

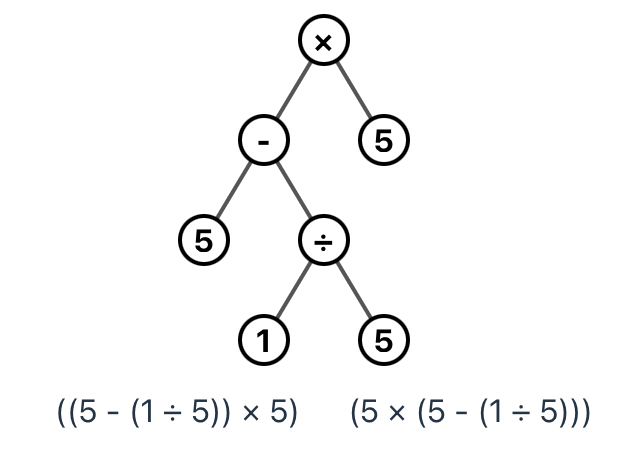

Once I coded up the solver – I could finally find the answer to if 5, 5, 5, 1 was solvable. Turns out: it is! I don't think if I spend half an hour could I have thought to subtract a fifth from 5 and then multiply by 5.

Turns out there are some pretty interesting expressions that I'd never have thought of. There are also a lot of numbers that don't work: like 10, 10, 10, 10. Many impossible games are all repeats, or have lots of 7s or 9s. I'd guess that's because 7 and 9 don't have many divisors and they're kinda large numbers, which ends up being annoying to work with.

The expressions with the most values: 1, 1, 3, 8 and 1, 1, 4, 6.

There are 16 games with 1 solution: 1115, 1277, 1558, 1668, 2555, 2599, 3355, 3490, 3555, 4400, 5555, 5588, 5599, 5500, 6699, 6790.

There are only 128 games with 0 solutions (out of 10,000).

Try It Yourself

I encourage you to try the app I made. Happy puzzling.

| [1] | The proof for this follows. Consider at the root node the number of leaves on each subtree. There are 3 options: \((1,3)\), \((2,2)\), \((3,1)\) since there have to be 4 numbers in the tree, and at least 1 on either side. Then think about the number of subtree shapes: for 1 node, there's only the trivial tree, for 2 nodes there's only one option for how to connect it, and for 3 nodes, we can divide that into \((1,2)\) and \((2,1)\), so 2. Thus, we get 2 options for the \((1,3)\)s and 1 option for \((2,2)\) which gives us 5 total. |